Comparison of Memory Types Available for Your Product

Learn about the types of memory available for microcontrollers, and their various advantages and limitations.

Every electronic system that has some kind of microcontroller, or microprocessor, needs to have some memory attached to it.

This memory holds the program that the processor executes. It also holds the data that the program requires, or produces. This data may come from sensors, or is some intermediate result of the running program, or is simply to be saved or displayed. In an ideal world, there should be only one kind of memory.

However, the currently available memory technologies require the user to compromise among several factors: speed of access, cost per bit, and data retention performance.

For example, the hard drive in most PC’s can store a large amount of data at a relatively low cost, and its data is not lost when the PC is powered off. It is, however, quite slow.

The main memory of the PC is more expensive relative to the amount of data it can store, and it loses the data when the PC is turned off. It is, however, much faster than a hard drive.

Memories can be broadly classified into two main categories: volatile and non-volatile. A volatile memory will lose its contents when power is removed. On the other hand, a non-volatile memory will retain its contents when power is removed.

In general, non-volatile memory is slower, but costs less per bit, than volatile memory. It is used to store start-up, or boot-up, code and user-saved data. Lower speed systems usually store the entire program in non-volatile memory.

Volatile memory is mostly used to store intermediate data generated by the system, or, in higher speed systems, the currently running program is loaded from non-volatile into volatile memory to take advantage of its higher speed.

Non-volatile memory

Almost all electronic non-volatile memory uses the same underlying technology to store a single bit of data.

Each bit value is essentially determined by the presence or absence of charge trapped in a small insulated block of silicon that in turn act like the gate of a MOSFET. The charge on this floating gate determines whether the MOSFET channel is conductive or not, thus its logic level.

Charge injection into, or removal from, this insulated gate is accomplished by applying a high voltage of the proper polarity through another gate. Because of this, all non-volatile memories share some basic characteristics.

One is that to overwrite a memory bit, it has to be first erased before writing. Also, it has a wear-out mechanism that causes it to eventually fail after many write cycles.

The difference among them is how those memory bits are organized in the chip, which then determines how easily and how fast they can be accessed.

So, when talking about non-volatile memory, a few additional factors besides speed and cost per bit come into play. This differentiation also gives rise to different names for the different types of non-volatile memory.

Flash memory

These are used as the main program memory in microcontrollers and as start-up program storage in PC’s. The memory is usually organized in basic units call pages, each containing a given number of bytes.

These pages are then organized in blocks. Before writing any information, its containing page has to be entirely erased first, causing some delays.

There are two main sub-kinds of flash memory – NAND and NOR. They have differing characteristics that make them suitable for different applications.

NOR flash is used as Execute In Place (XIP) memory. That is, programs can be stored, and run, directly from this type of memory. It is generally faster than NAND flash, but also more expensive.

NAND flash is typically used in Solid State Drives, USB drives, and is also the underlying type used in SD cards.

EEPROM

EEPROM (Electrically Erasable Programmable Read Only Memory) memory is quite slow, and relatively expensive. What EEPROM offers in return is ease of access. Instead of accessing entire pages as with Flash memory, with EEPROM bytes can be individually written and erased, making them suitable for storing configuration and user information in embedded applications.

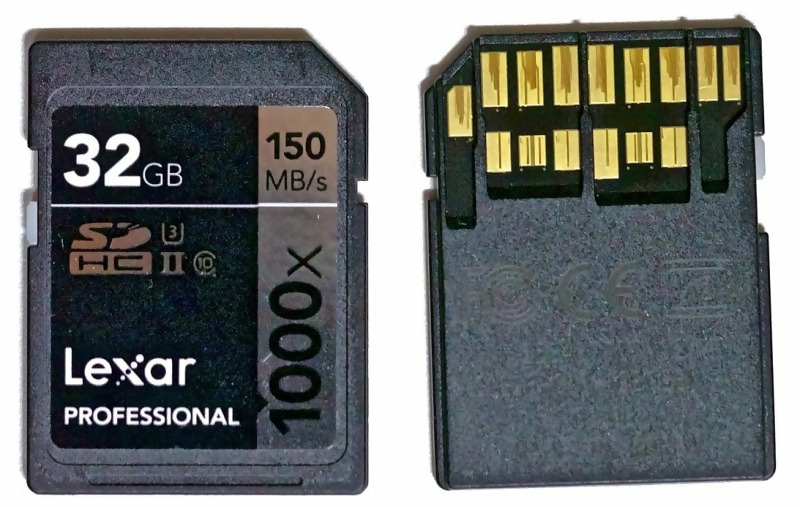

SSD and SD

Solid State Drives (SSD), and SD (Secure Digital) cards, both use NAND flash memory, and the data is accessed in large chunks. The main difference is that SSD’s are designed to be more reliable, especially when accessed as frequently as an ordinary hard drive.

Special error detecting and correcting, and wear leveling circuitry, is employed to reduce the inherent shortcomings of the base technology.

SD cards, by virtue of their size, do not typically have the storage capacity, or the sophisticated reliability enhancements, of their SSD counterparts. Hence they are primarily used in applications requiring less frequent access to data.

Discrete flash memory chips become exceptionally expensive in moderate volumes once you exceed a few MB of storage.

So, if your product requires GB of flash memory then in most cases it will be more economical to embed an SD memory card, at least until you reach a production volume high enough to obtain reasonable pricing on high-density discrete flash chips.

Other types of non-volatile memory

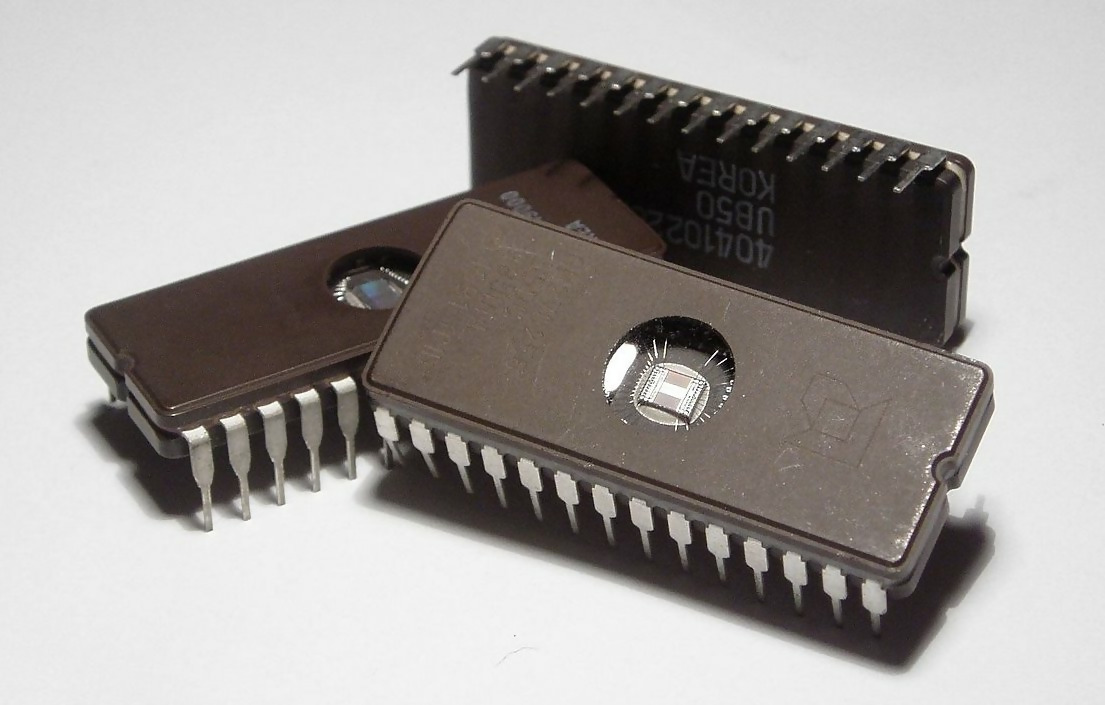

This section briefly describes some other types of non-volatile memory that were commonly used in the past.

The first one is the Read-Only Memory, or ROM. This was a chip that was programmed at the time of manufacture, and could not be changed afterward.

Then there was the Programmable ROM, or PROM. PROM was basically a one-time programmable memory chip.

Then along came EPROM memory (Erasable Programmable ROM). This chip has a small window to allow the contents to be erased using ultra-violet light. After erasure an EPROM could then be reprogrammed.

Summary of common non-volatile memory

Table 1 below compares the different attributes of each of the main types of non-volatile solid state memories.

| Attribute | NOR-Flash | NAND-Flash | EEPROM | Notes |

| Cost per bit | Low | Very low | Moderate | |

| Erase speed | Moderate | Moderate – Fast | low | |

| Write speed | Moderate | Moderate- Fast | low | |

| Read speed | Fast | Moderate | low | |

| Write endurance | >10000 | >10000 | >10000 | Depends on temperature. |

| Storage endurance | >20 years | >20 years | 20 to >100 years | Depends on storage temperature and prior number of write cycles. |

| Typical uses | Program code storage for direct execution by the processor. | Large amount of storage such as executable files, user files, pictures etc. | User-configuration, calibration values. |

Table 1 – Non-volatile memories

Volatile memories

Volatile memories, or Random Access Memory (RAM), are memories that will keep their contents only for as long as they remain powered. In this category, there are two broad classifications: static and dynamic.

A dynamic RAM, or DRAM, cell not only needs to be powered to keep its contents, but even then it will gradually lose its contents if it is not periodically refreshed.

Static RAM, or SRAM, on the other hand will simply keep its contents for as long as power is applied. So, why would an application use SRAM or DRAM instead of any of the previously described non-volatile types?

The answer is speed and ease of access. RAMs are much faster, and they can be accessed randomly. It is possible to simply write to, or read from, any memory location without worrying about pages or blocks, and at very fast speeds.

The downside is RAM in general costs more per bit. So, most computing systems generally have a combination of RAM and flash, each one fulfilling roles where their attributes can be optimally used.

In the broad RAM category, the SRAM is still faster than the DRAM, but it also costs more per bit. That’s because an SRAM cell requires four to six transistors whereas a DRAM cell requires only one. Hence, in a given-sized chip, many more DRAM cells can be packed together than SRAM cells.

The DRAM memory does require a controller that automatically performs the periodic refresh, however. So, using DRAM instead of SRAM only makes sense if the cost of this controller can be absorbed over a large enough memory size.

SRAM is used in cases where its higher access speeds are absolutely required, and where the memory size is relatively small.

Thus, SRAM is found in microcontrollers where the small amount of static memory does not justify the additional expense of a DRAM controller. SRAM is also used as high-speed cache memory inside microprocessors because of it’s fast access speed.

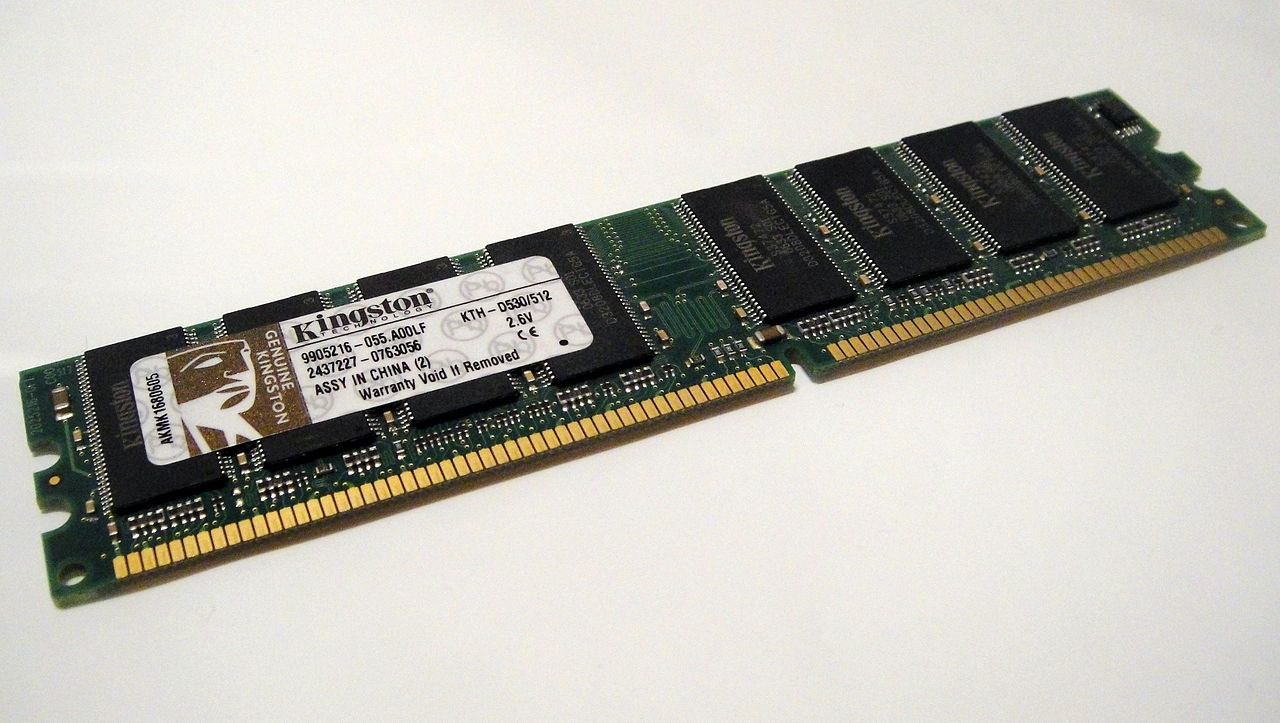

Types of DRAM

DRAMs come in many types, with the latest being DDR4. The original DRAM was replaced by FPRAM (Fast Page RAM), then EDO RAM (Extended Data Output RAM), and finally by Synchronous DRAM, or SDRAM.

Successive generations of SDRAM included Double Data Rate (DDR) SDRAM, followed by DDR2, DDR3 and, currently, DDR4.

While each new generation of SDRAM made some improvements over the previous generations, it should be noted that the basic dynamic RAM cell itself only had modest speed increases over the generations.

The packing density, or total number of bits packed into a single chip, on the other hand, did increase a lot. However, the major improvements going from SDRAM to DDR4 have been achieved in terms of data transfer rates and power consumption per bit.

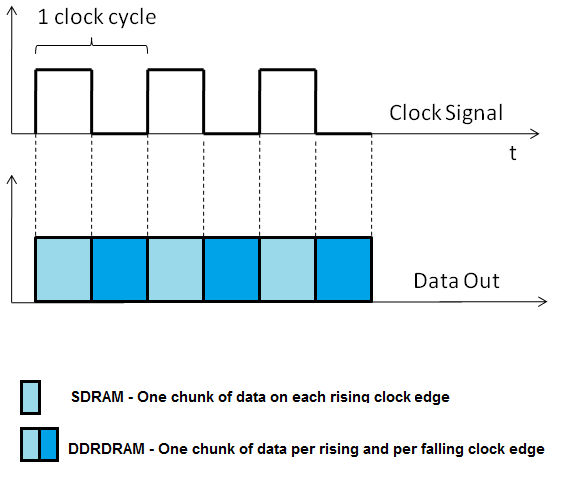

SDRAM is the base for all modern DRAM memories. DRAM memories prior to SDRAM were asynchronous, meaning that after a read request, the requested data appeared whenever it appeared. In SDRAM, the data is synchronized with the memory access clock.

After the SDRAM receives a read command, for example, it starts delivering the data after a specified number of clock cycles. This number is known as Column Address Strobe, or CAS, latency, and is a fixed number for a given memory module.

Furthermore, in SDRAM, this data delivery is always synchronized to an edge of the memory clock. So, the processor knows exactly when to expect the data it has requested.

DDR DRAM

The SDRAM previously described was also known, retroactively, as SDR, or Single Data Rate, SDRAM. The next evolutionary step was the DDR, or Double Data Rate, SDRAM.

Figure 3 shows the difference in the timing of SDR and DDR SDRAM. Note that in this figure the CAS latency is not shown. The read signal would have been a few clock cycles earlier than the actual beginning of the data transfer shown.

DDR2, DDR3, and DDR4

While the jump from SDR to DDR involved transferring data on both the rising and falling clock edges, DDR2 to DDR4 SDRAM get their increasingly higher data transfer speeds by mainly using some clever tricks.

It was mentioned earlier that DRAM technology access speed has not changed much due to limitations with the basic technology. At most, this basic access rate has doubled. Yet, as can be seen in Table 2 below, the transfer rate has steadily increased.

| Type | Basic access rate (MHz) | Prefetch depth | Data rate (Million Transfers/sec)* | Transfer rate (GB/sec) | Operating voltage (V) |

| SDR | 100 – 166 | 1n | 100 – 166 | 0.8 – 1.3 | 3.3 |

| DDR | 133 – 200 | 2n | 266 – 400 | 2.1 – 3.2 | 2.5 -2.6 |

| DDR2 | 133 – 200 | 4n | 533 – 800 | 4.2 – 6.4 | 1.8 |

| DDR3 | 133 – 200 | 8n | 1066- 1600 | 8.5 – 14.9 | 1.3 – 1.5 |

| DDR4 | 133 – 200 | 8n | 2133 – 3200 | 17 – 21.3 | 1.2 |

Table 2 – Quick comparison of DDR SDRAM

Without going into too many advanced technical details, one of the earlier mentioned tricks is to increase the data width. If the memory is internally organized such that during one access many bits are read all at once, then the aggregate data transfer rate will be increased.

Since memory is usually accessed sequentially the CAS latency does impose some delay between the instance when a read command is issued, and that at which the data is ready.

Therefore, another trick is for the memory to be arranged in such a way that the memory controller can issue multiple reads, or prefetch subsequent data. This allows the memory chip to have the next data chunk ready sooner for the next transfer.

Finally, advances in silicon technology mean that the operating voltage can be lowered, which consequently lowers the power required per bit, allowing larger memory sizes for the same power consumption.

Conclusion

The majority of products will require both non-volatile and volatile memory. But the specific types of memory required will depend on the specific product.

The memory you select for your product will have a major impact on performance, cost and power consumption. Selecting the right types of memory for your new product is a critical decision.

As with all things in engineering there are always tradeoffs between the various design choices. Now that you have a solid understanding of the basics of various memory types you should be in a position to choose the best types of memory for your new product.

One could add Ferroelectric RAM (FRAM) to the list.

I remember when EDO (Extended Data Out) DRAM became available. The previous generation of DRAM had no competition, so most people forgot it was called FPM (Fast Page Mode) DRAM, so most people just called it NON-EDO. EDO had a subtle change in timing in that the Data Pin(s) retained active output drive beyond the end of the /CAS (Column Address Strobe) signal. So the data output was extended. The name clearly described the functionality. The upshot being that each successive word in a burst could be read one clock cycle sooner. So the next read cycle could start before the present cycle was finished. Very small design change, noticeably faster memory access.

When they were new, EDO DRAMS were hard to get. But it turned out that FPM DRAMS would work with EDO timing, because capacitance on the data bus would retain the data for the extended clock period.

Maybe this is only interesting to memory design engineers.

Interesting, thanks Raleigh for sharing!

Great write up. Right to the point. A quick question though. Based on table-2, can (close voltage) memory types be interchangeably used on the same motherboard, say DDR3 and DD4 (or, be mixed)? Thanks,.

Hi Deniz,

The short answer is no they cannot be mixed. One simple reason is the modules are not physically compatible. DDR3 modules have 240 pins, while DDR4 module shave 288 pins. Also, the keying notches on the memory modules are in different positions, to prevent just such a case.

Thanks for your prompt reply. Sorry, I was not made it too clear (realized after hitting submit but could not edit ..). I meant using two different voltages 1.3V and 1.5V of -say- DDR3 memories be safe (or feasible) to use together on the same board. Some people mention that 1.5V RAMs are only overclocked version of 1.3V, if true.